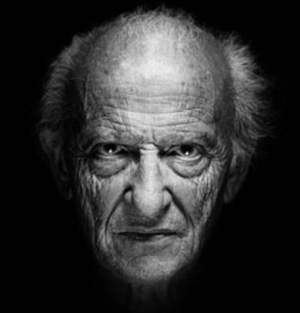

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Discurso inaugural de presentación ante el Armor Insitutute de Chicago el 21 de octubre de 1938

El arquitecto alemán Ludwig Mies van der Rohe en su estudio de Chicago

El arquitecto alemán Ludwig Mies van der Rohe en su estudio de Chicago

Toda educación debe dirigirse, en primer lugar, hacia el lado práctico de la vida. Pero si alguien debe hablar de la educación verdadera, entonces debe ir más allá y alcanzar la esfera personal y aspirar a una conformación del ser humano.

El primer objetivo debe ser cualificar a la persona para mantenerse por sí misma en la vida cotidiana. Se trata de dotarla con los conocimientos y habilidades necesarios para este propósito. El segundo objetivo está dirigido hacia la formación de la personalidad. Debería mejorarse para que pueda hacer un uso correcto de su conocimiento y habilidad.

La educación genuina no apunta sólo a fines específicos, sino también a una apreciación de los valores. Nuestros objetivos están ligados a la estructura especial de nuestra época. Los valores, por el contrario, están anclados en el destino espiritual de la humanidad. Los fines, hacia los que nos esforzamos, determinan el carácter de nuestra civilización, mientras que los valores que establecemos determinan nuestro nivel cultural.

Aunque las aspiraciones y los valores son de naturaleza y origen diferente, es cierto que están estrechamente asociados. Porque nuestras estándares de valor están relacionados con nuestras aspiraciones, y nuestras aspiraciones obtienen su significado de esos valores. Ambos conceptos son necesarios para establecer la plena existencia humana. Uno afianza a la persona en su existencia vital, pero es sólo el otro el que hace posible su existencia espiritual.

Así como estos propósitos tienen una validez para toda conducta humana -incluso para la más mínima diferenciación de valor- son también mucho más relevantes en el ámbito de la arquitectura. La arquitectura está arraigada en sus formas más sencillas por completo a lo útil, pero se expande sobre todos los grados de valor hacia la esfera más alta de la existencia espiritual, en la esfera de lo significante: el territorio del arte puro.

Así como estos propósitos tienen una validez para toda conducta humana -incluso para la más mínima diferenciación de valor- son también mucho más relevantes en el ámbito de la arquitectura. La arquitectura está arraigada en sus formas más sencillas por completo a lo útil, pero se expande sobre todos los grados de valor hacia la esfera más alta de la existencia espiritual, en la esfera de lo significante: el territorio del arte puro.

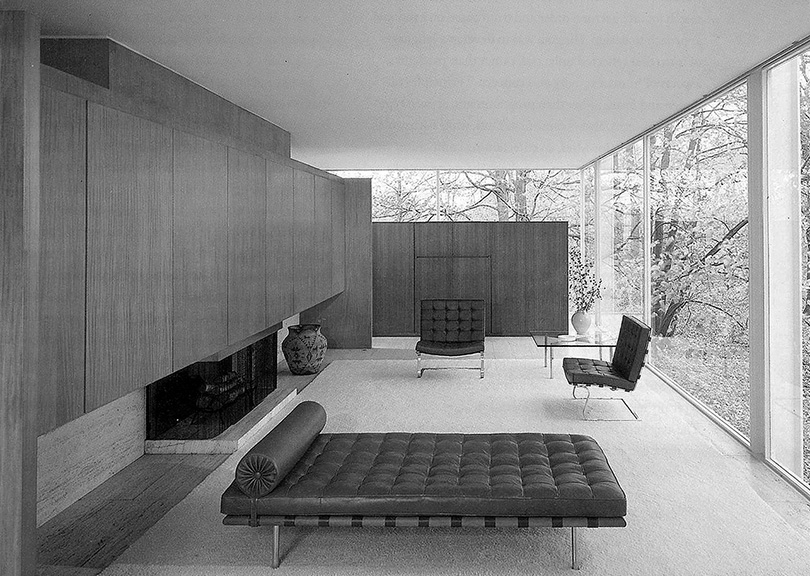

Interior de la Casa Farnsworth en Plano Illinois. Mies van der Rohe, 1945-1951

Cualquier forma de educación arquitectónica debe tener en cuenta esta circunstancia si lo que se pretende es alcanzar su objetivo. Debe tener en cuenta esta relación orgánica. En realidad, no puede ser otra cosa que un despliegue activo de todas estas relaciones e interrelaciones. Debe hacer evidente, paso a paso, lo que es posible, lo que es necesario y lo que es significante.

Si la educación tiene algún sentido, entonces consiste en formar el carácter y desarrollar la comprensión. Debe alejarnos de la irresponsabilidad de la opinión, hacia la responsabilidad de la comprensión, el juicio y la comprensión; debe alejarnos de la esfera del azar y de la arbitrariedad hacia la luz clara del orden intelectual. Por lo tanto guiamos a nuestros estudiantes sobre el camino disciplinar desde lo material y a través de la función hacia la forma.

Estamos decididos a conducirlos hacia el mundo saludable de los edificios primitivos, donde cada golpe de hacha significaba algo y donde cada corte de cincel era una verdadera declaración. ¿Dónde aparece el entramado estructural de un edificio con mayor claridad que en los edificios de madera de nuestros antepasados?. ¿En dónde más hay una unidad similar entre material, construcción y forma? Ahí yace escondida la sabiduría de toda la raza humana. ¡Qué gran sentido tiene el material, y qué poder de expresión proclaman estos edificios! ¡Qué calidez irradian y qué hermosos son!

En los edificios de piedra encontramos lo mismo. ¡Qué sentimiento natural se expresa en ellos! ¡Qué comprensión clara de la materialidad, qué seguridad en su uso, qué sentido para lo que puede y debe hacerse en piedra!. ¿Dónde más encontramos tal riqueza de estructura? ¿Dónde encontramos fuerza más vigorosa y mayor belleza natural que aquí? ¿Con qué evidente claridad un techo de vigas descansa sobre estos viejos muros de piedra? y ¿Con qué sentimiento se recorta una puerta en ellos?

¿Dónde más pueden progresar los jóvenes arquitectos que en el aire fresco de este sano mundo? y ¿dónde más deberían aprender a trabajar de manera simple y prudente que con estos maestros desconocidos?

El ladrillo es otro maestro. ¡Qué inteligente es esta pieza pequeña y práctica, útil como lo es para todo propósito. ¡Qué lógica muestra su unión; Qué vivacidad en sus uniones! ¿Qué riqueza posee la más simple superficie de la pared! Y así y todo, ¡qué disciplina impone este material!

Así, cada material posee su especialidad que uno debe conocer para poder trabajar con ellos. Esto también es válido para el acero y el hormigón. No esperamos absolutamente nada de los materiales en sí mismos, sino sólo a través del uso correcto de ellos. Por ello, los nuevos materiales tampoco nos aseguran lo superior en sí mismos. Cualquier material sólo vale en cuanto lo que podemos hacer con él.

Así como estamos orientados a conocer los materiales, también estamos decididos a conocer la naturaleza del propósito para el que construimos. Los analizaremos claramente. Estamos decididos a saber cuál es su contenido; en una residencia eso será realmente diferente a cualquier otro tipo de edificio. Queremos saber lo que puede ser, lo que debe ser, y lo que no debe ser. Por lo tanto, debemos llegar a lo esencial. Examinaremos así cada función que pueda aparecer y determinar su carácter y hacer de su carácter la base de nuestro concepto y forma.

Así como buscamos el conocimiento de los materiales, así nos damos cuenta de la naturaleza de los usos para los que construimos, y también debemos aprender a comprender el ambiente espiritual e intelectual en el que nos encontramos. Este es un requisito previo para una conducta adecuada en el ámbito de la cultura. Aquí, también, debemos saber lo que existe, porque somos dependientes de nuestra época.

Por lo tanto, debemos aprender a reconocer las fuerzas nutrientes e irresistibles de nuestro tiempo. Debemos hacer un análisis de su estructura; es decir, de las fuerzas materiales, funcionales e intelectuales de hoy en día. Debemos entender en qué nuestro tiempo es época es similar al de épocas anteriores, y en que difiere de ellas.

Aquí el problema de la tecnología vendrá a ser la brújula del estudiante. Debemos intentar plantear preguntas genuinas: preguntas sobre el valor y el significado de la tecnología. Demostraremos que no sólo nos ofrece poder y magnitud, sino que también incorpora los peligros, que contiene el bien y el mal, y que aquí la humanidad debe decidir correctamente.

Sin embargo, cada decisión conduce a una definitiva aclaración de principios y valores. Por lo tanto, tendremos que dilucidar los posibles principios de orden y aclarar sus bases.

Señalaremos el principio mecánico del orden como una intensidad superior a la tendencia al materialismo y al funcionalismo. No satisface nuestro sentimiento el que “los medios” tengan solo una mera función servil, ni que sean suficientes para cubrir nuestro interés por la dignidad y el valor.

El principio idealista del orden, en el otro extremo, puede, con su énfasis en lo ideal y en lo formal, ni satisfacer nuestro interés por la verdad y la simplicidad ni alcanzar el lado práctico de nuestro intelecto.

Tendremos que hacer que el principio orgánico del orden sea claro como una escala para establecer el significado y la proporción de las partes y su relación con el todo.

Adoptaremos este último principio como la base de nuestro trabajo.

El largo camino desde el material a través de la función a la forma tiene un solo objetivo: crear el orden que se diferencie de la profana confusión de nuestros días. Queremos, sin embargo, un orden que da a cada cosa su lugar apropiado. Queremos dar a todo aquello que es debido, de acuerdo con su naturaleza.

Estamos empeñados a hacerlo de una forma tan perfecta que el mundo de nuestra creación empieza a florecer desde dentro. No queremos nada más

Nada expresa mejor la voluntad y el significado de nuestro trabajo que las palabras profundas de Tomás de Aquino:

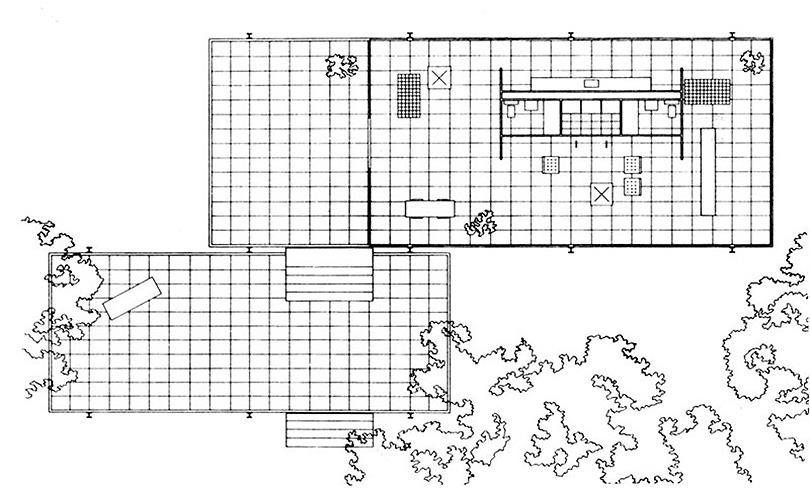

“LA BELLEZA ES EL FULGOR DE LA VERDAD.” Planta de distribución de la Casa Farnsworth en Plano Illinois. Mies van der Rohe, 1945-1951

Planta de distribución de la Casa Farnsworth en Plano Illinois. Mies van der Rohe, 1945-1951

ARCHITECTURE AND TRUTH

Banquet Speech at the Palmer House Hilton. 21/10/1938

Mies van der Rohe Society. Illinois Institute of Technology. Consultado 30/01/2017

Any education must be directed, first of all, towards the practical side of life. But if onemay speak of real education, then it must go farther and reach the personal sphere and lead to a molding of the human being.

The first aim should be to qualify the person to maintain himself in everyday life. It is to equip him with the necessary knowledge and ability for this purpose. The second aim is directed towards a formation of the personality. It should qualify him to make the right use of his knowledge and ability.

Genuine education is aimed not only towards specific ends but also towards an appreciation of values. Our aims are bound up with the special structure of our epoch. Values, on the contrary, are anchored in the spiritual destination of mankind. The ends, towards which we strive, determine the character of our civilization, while the values we set determine our cultural level.

Although aspirations and values are of different nature and of different origin, they are actually closely associated. For our standards of value are related to our aspirations, and our aspirations obtain their meaning from these values. Both of these concepts are necessary to establish full human existence. The one assures the person his vital existence, but it is only the other that makes his spiritual existence possible.

Just as these propositions have a validity for all human conduct, even for the slightest differentiation of value, so are they that much more binding in the realm of architecture. Architecture is rooted with its simplest forms entirely in the useful, but it extends over all the degrees of value into the highest sphere of spiritual existence, into the sphere of the significant: the realm of pure art.

Detalle de la plataforma de acceso a la Casa Farnsworth en Plano Illinois. Mies van der Rohe, 1945-1951

Every architectural education must take account of this circumstance if it is to achieve its goal. It must take account of this organic relationship. It can, in reality, be nothing other than an active unfolding of all these relationships and interrelationships. It should make plain, step by step, what is possible, what is necessary, and what is significant.

If education has any sense whatever, then it is to form character and develop insight. It must lead us out of the irresponsibility of opinion, into the responsibility of insight, judgment, and understanding; it must lead us out of the realm of chance and arbitrariness into the clear light of intellectual order. Therefore we guide our students over the disciplinary road from material through function to form.

We are determined to lead them into the wholesome world of primal buildings, where every axe stroke meant something and where every chisel cut was a veritable statement. Where does the structural fabric of a building appear with greater clarity than in the wood buildings of our forefathers? Where else is there an equal unity of material, construction, and form? Here lies concealed the wisdom of the entire race. What a sense for the material, and what a power of expression these buildings proclaim! What warmth they radiate and how beautiful they are!

In stone buildings we find the same. What natural feeling is expressed by them! What clear understanding for material, what sureness in its use, what a sense for that which can and should be done in stone! Where else do we find such a richness of structure? Where do we find more healthy strength and greater natural beauty than here? With what self-evident clarity a beamed ceiling rests on these old stone walls, and with what feeling one cut a door in them!

Where else should young architects grow up than in the fresh air of this wholesome world, and where else should they learn to work simply and prudently than with these unknown masters?

Brick is another schoolmaster. How clever is this small, handy unit, useful as it is for every purpose! What logic its bonding shows; what liveliness its jointing! What richness the simplest wall surface possesses, yet what discipline this material imposes!

Thus each material possesses its special which one must know in order to be able to work with them. That is also true of steel and concrete. We expect absolutely nothing from the materials in themselves, but only through our right use of them. Then, too, the new materials do not insure superiority. Any material is only worth that which we make out of it.

Just as we are determined to know materials, so are we determined to know the nature of the purposes for which we build. We will analyze them clearly. We are determined to know what their content is; wherein a dwelling is really different from another kind of building. We want to know what it can be, what it must be, and what it should not be. Therefore, we must get at their essentials. Thus we will examine every function which appears and determine its character and make its character the basis for our conception and our form.

Just as we procure a knowledge of materials – just as we acquaint ourselves with the nature of the uses for which we build, so must we also learn to comprehend the spiritual and intellectual environment in which we find ourselves. That is a prerequisite for proper conduct in the cultural sphere. Here, too, we must know what exists, for we remain dependent upon our epoch.

Therefore we must learn to recognize the sustaining and compelling forces of our times. We must make an analysis of their structure; that is, of the material, the functional, and the intellectual forces of today. We must clarify wherein our epoch is similar to former epochs, and wherein it differs from them.

Here the problem of technology will come within the student’s compass. We will try to propound genuine questions: questions on the value and meaning of technology. We will demonstrate that it not only offers us power, and magnitude, but that it also embraces dangers, that it contains good and evil, and that here mankind must decide aright.

Yet every decision leads to a definite clarification of principles and values. Therefore we will elucidate the possible principles of order and clarify their bases.

We will mark the mechanical principle of order as an over emphasis of the materialistic and functional tendency. It does not satisfy our feeling that “the means” is a menial function, nor does it satisfy our interest in dignity and worth.

The idealistic principle of order, on the other hand, can, with its over emphasis on the ideal and the formal, neither satisfy our interest in truth and simplicity, nor the practical side of our intellect.

We will make the organic principle of order clear as a scale for establishing the significance and proportion of the parts and their relation to the whole.

We will adopt this last principle as the basis of our work.

The long road from the material through function to form has only one goal: to create order out of the unholy confusion of today. We want, however, an order which gives everything its proper place. We want to give to everything that which is its due, in accordance with its nature.

We are determined to do that in such a perfect way, that the world of our creation begins to flower from within. We want no more – nor can we do more.

Nothing will express the aim and meaning of our work better than the profound words of Thomas Aquinas:

“BEAUTY IS THE RADIANCE OF THE TRUTH.”

Mies van der Rohe descansando en su apartamento de Chicago.